Climate Change Deliberation: Taking Occam’s Razor to Proxy Data

Written by Robert T. Smith

It is quite often the case that the simplest explanation is the correct explanation. The namesake for this principle comes from the English philosopher and theologian, Franciscan friar William of Ockham. It is called Occam’s razor. From various sources, Occam’s razor is a principle of parsimony or frugality used in logic and problem-solving. It states that among competing hypotheses, the hypothesis with the fewest assumptions should be selected. Perhaps Occam’s razor can be appropriately applied to many of our current issues.

A particular example is the theory of anthropogenic (human-induced) global warming. Our earth has gone through many periods of naturally occurring global warming and cooling. We know the Vikings colonized and established agriculture in Greenland during the Medieval Warm Period, and we know of the dark days of a frozen Thames River in the U.K. during the Little Ice Age. Many point to greenhouse gases and climate change as a reason to regulate carbon. Occam’s razor, on the other hand, would inform us that climate change has natural causes.

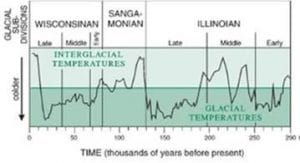

As depicted in this illustration (Pennsylvania Geologic Survey, 1999), in the larger scale of the earth’s history, we are at a relatively warm period. The point of this illustration (based on a long-standing study that has influenced our current understanding of the earth’s history) is the historic nature of dramatic climate change without any influence by man, and our current position on the higher end of the historic temperature fluctuations. Based on this illustration, if past is prologue, we probably should keep our winter coats.

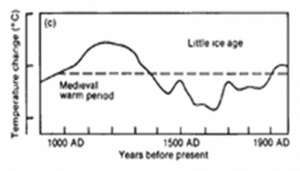

The following graph depicts the Medieval Warm Period transitioning to the Little Ice Age (this is another long-standing study, done in 1990 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). This graph shows the historic fluctuation of global temperatures to the present that was the consensus understanding of more recent warming and cooling periods, included in the IPCCs assessment.

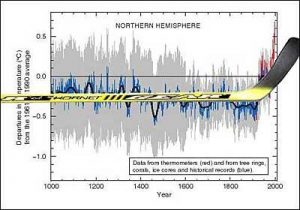

Subsequently, a multitude of proxy data and statistical manipulation more recently transitioned this simple understanding into the hockey stick theory of global temperatures. The hockey stick theory suggests the steady-state temperatures of the earth (the hockey stick handle) were triggered dramatically upward (the blade of the hockey stick) by man’s activity beginning in the 1900s. This new theory does not show a Medieval Warm Period bump or Little Ice Age trough.

The improbability of flattening the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age with proxy data and statistics speaks to the essence of Occam’s razor. The proxy data relied upon as the basis for the statistical assessment themselves have a multitude of variability, unknowns, and extraneous considerations. The use of statistics to defend a hypothesis can be subjective and several experts have critiqued how statistics were used in this case to support the hockey stick theory (see Stephen McIntyre, Ross McKitrick, and Richard Mueller). The principle of Occam’s razor, however, suggests that there should be no dramatic changes in our laws and economy to respond to the relatively new allegations of man-induced global warming.

Scientifically known facts are that the atmosphere is comprised of approximately 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 0.04% carbon dioxide, with the remaining various trace gases. Logically considered then is that the concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere is a very small proportion of the gases present in the atmosphere. Human activity accounts for less than 4% of global carbon dioxide emissions. That is 4% of the 0.04% of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. According to NASA, water vapor is unequivocally by far the most abundant contributor to the greenhouse effect.

This man-made contribution to the atmospheric CO2 concentration is not large and arguably may not appreciably contribute to the greenhouse effect. But when controlling carbon seems to be the end game for some, any amount of man-made CO2 can be pointed to as evidence for the need for laws and regulations.

While much of the world struggles with even the basics for life—sufficient food, shelter, clean water, and basic disease prevention—only our portion of the “developed” world tilts at the windmill of controlling the Earth’s climate. Shall we spend our efforts wisely and maintain our own economic abundance so that we may help others and ourselves while others in the world, such as China, continue with their emissions? We provide huge contributions throughout the world to assist poor nations to grow crops, access clean water, overcome diseases, and respond to natural and man-made disasters. Or shall we deal with the relatively small amount of man-caused CO2 emissions, cripple ourselves economically with burdensome regulations and taxation, and diminish our ability to help ourselves and others?

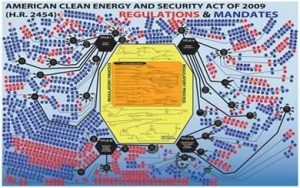

Consider the below diagram from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which illustrates the logical legal consequences of the 2009 American Clean Energy and Security Act. A multitude of regulations and mandates would flow from the various organs of government.

As illustrated, the control of carbon would touch every aspect of our daily lives. We have been warned repeatedly for at least the past three decades that we have just a few years remaining to save the earth. While much has been written and debated about global climate change over many years, the basic aspects of the issue haven’t changed; we are asked to forget things we once knew and ignore the simplest hypothesis that the earth’s climate is ever changing. Occam’s razor.

This article was originally published at The Institute for Faith & Freedom.

Robert T. Smith is the co-owner of an environmental consulting company,

environmental scientist, and published opinion writer.