GOP Candidates’ Quest for the Highly Religious Protestant Vote

Written by Frank Newport

Mike Huckabee’s official entrance into the Republican race for president this week underscores the importance of a particular segment of the Republican population — highly religious Protestant voters. Often called evangelicals, this segment is clearly the key target for Huckabee’s campaign. Huckabee attended Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, is a former Baptist minister, and as was the case in 2008, he clearly perceives this religious background to be a particular strength. Huckabee is not the only one vying for the affection of the highly religious Protestant segment, of course. Ted Cruz made his announcement in front of the student body at the evangelical Liberty University in Virginia. Jeb Bush made his own trek to Liberty University as the commencement speaker on May 9. Potential presidential candidate Scott Walker has been emphasizing his religious upbringing in Plainfield, Iowa, as the son of a Baptist preacher.

The term “evangelical” is a loose one, and there are a number of different ways to define it, including simply asking respondents if they are “evangelical.” For the purposes of this analysis, I’m looking at Republicans and independents who lean Republican who identify their denomination as Protestant or some other non-Catholic, non-Mormon Christian faith — and who we classify as highly religious based on their religious service attendance and their self-reported importance of religion.

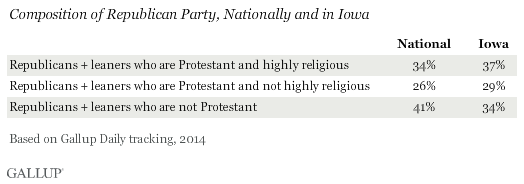

About 34% of the national Republican population meets this criteria as being “highly religious Protestant Republicans” or HRPR for short.

Of significant interest to declared or likely Republican candidates is the HRPR population in Iowa, where the first political contest of the election will take place next February, and whose value is considered to be far above the relatively modest number of delegates the state produces. Just recently, nine current or potential GOP presidential candidates showed up at the Point of Grace Church in a suburb of Des Moines, all of them intent on impressing the assembled congregation of evangelicals with their synchronicity of attitudes, beliefs, hopes and desires.

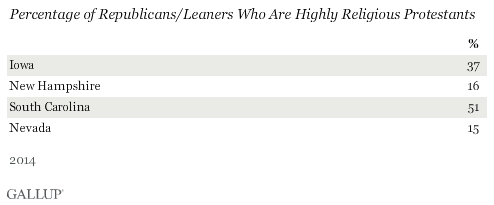

But Iowa’s concentration of HRPRs is just 37%, barely above the national average. Iowa has another 29% of its Republicans who are Protestants but not highly religious, and another third of the party consists of non-Protestants, mainly Catholics. Thus, unlike some other states that I’ll talk about shortly, Iowa does not have a particularly large HRPR population.

Iowa’s average ranking on this dimension is not surprising when one remembers that Iowa is a swing state precisely because it is about average on most political dimensions. Nevertheless, the point here is that the GOP candidates are battling it out over a slice of the voting pie in Iowa that is not unusually large, but presumably considered to be unusually potent, given the way in which HRPR voters can turn out in high numbers and have a disproportionate influence in their state’s unusual caucus system.

There are three other early caucus and primary states whose votes will be generating a lot of attention in February just as the presidential campaign gets underway — New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada. These states, unlike Iowa, are not average, and in fact contain very different profiles of Republican voters.

New Hampshire is the state, along with Iowa, that seems to be most on candidates’ travel agendas these days. But, as astute Gallup.com readers will certainly know by this time, New Hampshire is the second-least religious state in the union, just barely behind its western neighbor Vermont. It comes as no shock to find that only 16% of New Hampshire Republicans are HRPR, giving it one of the lowest such percentages across the 50 states.

Thus, Republican candidates campaigning in The Granite State are not nearly as likely to be emphasizing the same type of religiously-oriented themes, religious references and religious buzz words as they are in Iowa (and other states, as we will see). In fact, candidates would presumably be hard-pressed to find huge Protestant mega-congregations to use as venues in New Hampshire even if they were so inclined.

On the other hand, South Carolina offers a very robust audience of evangelically oriented GOP voters, with a HRPR percentage of 51%, tying for the fifth-highest percentage of any state. South Carolina is clearly a place where religious overtones from Republican candidates will find a very receptive audience, although it should be noted that Newt Gingrich, a converted Catholic, won South Carolina in 2012, and John McCain beat out Huckabee in South Carolina in 2008.

The final February caucus state is Nevada, which is about as dissimilar from New Hampshire as one could imagine geographically and topographically, but very similar to New Hampshire in the fact that it has only 15% HRPR. Mitt Romney won Nevada in both 2008 and 2012, in part owing to Nevada’s above average Mormon population and its proximity to Utah, where Romney’s name is well known.

This HRPR metric, of course, tells only a part of the highly complex picture that will ultimately determine who wins the GOP nomination. There is certainly not a one-to-one relationship between a candidate’s own religiosity and faith and his or her probability of winning a state’s delegates. Still, the degree to which candidates are already talking to and about evangelical Republican voters stands as a testimony to the perceived power of that group. Clearly that message will resonate much more fully in some states than in others.

Frank Newport, Ph.D., is Gallup’s Editor-in-Chief. He is the author of Polling Matters: Why Leaders Must Listen to the Wisdom of the Peopleand God Is Alive and Well.

This article was originally posted at the Gallup.com website.