I’m a Privileged American … Please Put Race Aside

Written by Dr. Gary L. Welton

I do not feel like a privileged person today when I watch Olympic competitions. These young white, black, and Asian athletes from around the world have been given incredible opportunities to train and specialize in their events. When I should have started such training as a child, I did not even know there was such a thing. When we had a functional television in our home, which was rare, we had atrocious reception.

I remember hearing Neil Armstrong’s famous words, but I could not see anything on the screen. I rarely participated in any after-school opportunities because it felt wrong to ask my parents to figure out how to get me home afterwards. Our central heating used a coal furnace, which I never successfully learned to fire. I slept in a sleeping bag all winter long.

In spite of the challenges, I was comfortable and happy with my life. I felt like a privileged American.

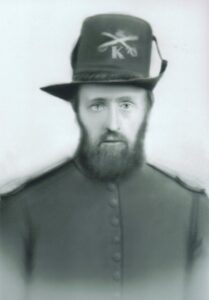

We were not privileged economically. My family had a history of poverty that dated from the Civil War. My great, great grandfather, Milo Welton, as a 40-year-old, saw his oldest teenage son, John, enlist in the Union Army to assist the efforts to establish freedom for all Americans by ending slavery in the United States. Milo apparently felt guilty that his son accepted this challenge when he himself had not done so, so he enlisted in the Union Army as well. Both lost their lives during the Civil War. John died of a gunshot wound to the chest. Records indicate that Milo died of malaria or dysentery. Milo is buried in Washington, D.C. at the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery, though his name is misspelled as “Walton” (we get that a lot). John is buried at the Cavalry Corps Cemetery in City Point, Virginia.

Milo Welton

As a result of supporting the effort to end slavery, my great, great grandmother had the task of rearing her younger children without the support of their father and oldest brother. The historical records provide little detail about their struggles, but my family heritage is not one of economic privilege.

My grandfather spent his working years as a farm hand, hiring himself out for brief periods of time when his assistance was needed, wherever he could find work. The family had to move frequently. My father reported that he lived in some 20 different houses from the time of his birth until he left home to join the Army Air Corps in World War II. His mother quickly learned not to unpack the family’s non-essential possessions.

My ancestors made a choice to risk their economic stability to support the rights and equality of all Americans. They paid a high price for that choice. The resulting family poverty directly impacted the children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. My economic heritage was not a privileged one because I am white. My white ancestors chose not to cash in on any privilege, but instead counted it an honor to support the rights of all Americans. My great grandfather grew up without his father (from age eight). As an adult he suffered through tornado, fire, and typhus, yet helped start one of the churches here in town. My mother worked cleaning houses to help pay the bills and buy the coal to heat the old house. My parents taught me that the choices we make in how we live our lives and treat others (whether they look like us or not) are more important than our economic status.

Because of our economic challenges, I did not have some of the opportunities that my classmates had, but I was a privileged person, not particularly because I was white or because I was male. Rather, I am a privileged American, with the opportunity to support freedom for all (whether they look like me or not).

I do not apologize for being a white American. My family paid a price to help establish freedom for all Americans. Please don’t call me racist, just because my skin is white.

Dr. Gary L. Welton is assistant dean for institutional assessment, professor of psychology at Grove City College, and a contributor to the Institute for Faith and Freedom, where this article was first published. He is a recipient of a major research grant from the Templeton Foundation to investigate positive youth development.